They’re just three letters, but what they represent may very well have spelled the difference between success and failure for some Genesee County businesses during the COVID-19 shutdowns, observers say.

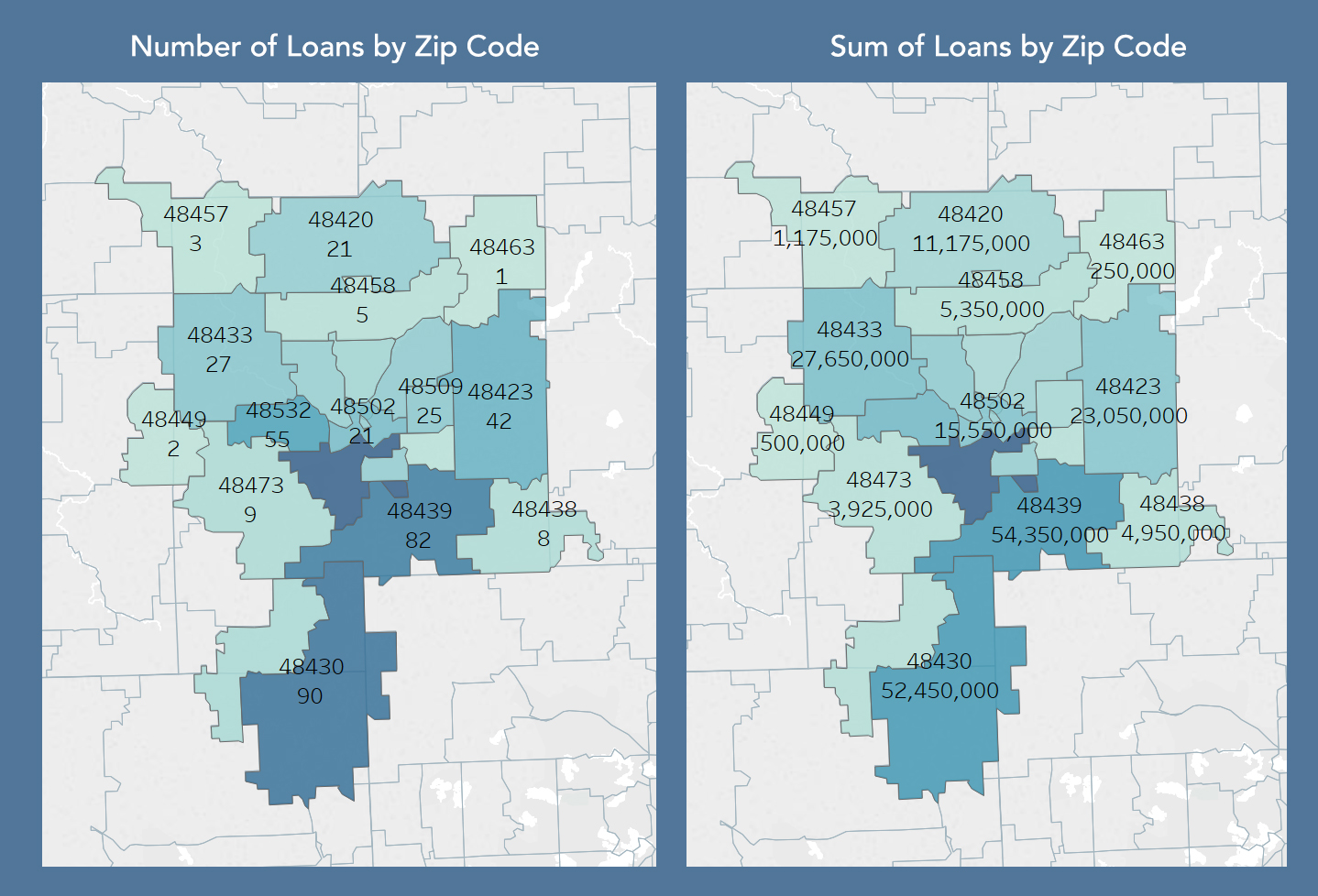

The federal PPP, or Paycheck Protection Program, pumped a total of more than $550 million into 3,862 Genesee County businesses when the U.S. Small Business Administration released the funds, statistics compiled by the Flint & Genesee Chamber of Commerce show.

“The number was just staggering to me,” said Tyler Rossmaessler, the Chamber’s director of economic development. “What strikes me is the sheer amount of government assistance that was poured into our economy.”

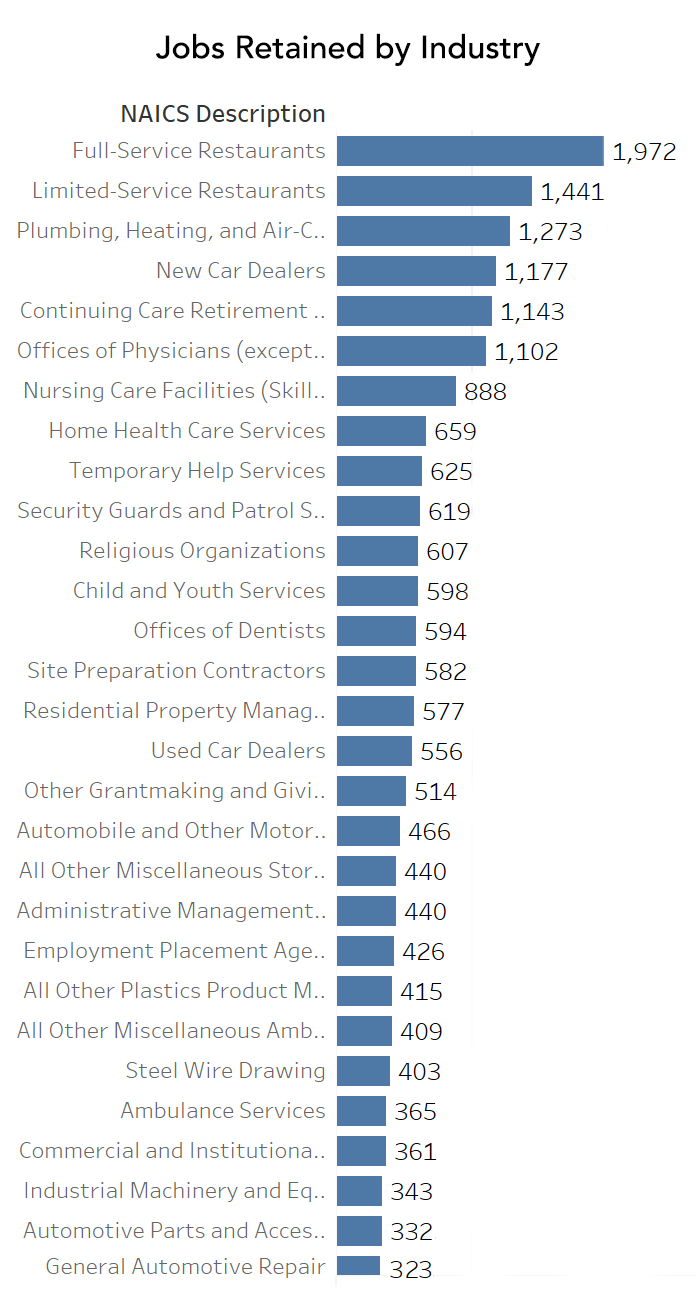

Another important statistic: County businesses used their PPP funding to retain 57,294 jobs, meaning a significant chunk of the county’s 140,000-person pre-pandemic workforce also benefited from the program.

The PPP was designed to provide a direct incentive for small businesses to keep their workers on payroll, and loans will be fully forgiven if at least 60 percent of the funds are used for payroll costs, with interest on mortgages, and rent and utilities constituting other eligible uses.

At John P. O’Sullivan Distributing, Inc., a Flint Township beer distributorship, PPP proceeds allowed the company to retain about 10 percent of its roughly 100-person workforce that otherwise would have been laid off while bars and restaurants were largely shut down and retailers weren’t accepting can and bottle returns this spring, said Controller Juliet Rachut.

“In applying for this loan, we were able to bring all those people back who work in those areas and not per se put them back in their existing roles, but place them in positions in the office and the warehouse to assist during that time,” she said.

The loan also allowed the company to continue health-care coverage for those employees and their families.

“That loan definitely helped us bridge the gap until bars and restaurants started reopening and retailers began accepting glass, aluminum and plastic again,” Rachut said.

And although bars and restaurants aren’t operating at full capacity, the company has largely returned the workers who serviced those segments to their regular positions.

Epic Machine President Mike Parker said his precision machining company used its PPP money to more efficiently manage its workforce, including providing incentives to its skilled trades workers who are in high demand from similar companies.

“Really, it was very, very beneficial to retain our good, qualified people here,” Parker said. “I’ve got a wonderful workforce, and we rewarded them to keep those good workers coming in. They’re getting enticed all the time. There are headhunters out there looking to try to find people. They’re all skilled workers and they’re being sought after.”

The company, which employs 27 workers, services over 200 foundries and pattern shops in 29 states. It has largely maintained operations throughout the entire pandemic because it serves many essential industries.

‘A positive story’

While many local businesses relied on PPP to keep the bulk of their workforce largely engaged, it likely served a more crucial role for others, said Chamber CEO Tim Herman.

“Really, it’s a positive story for our businesses. Some of these businesses would not have survived, I quite frankly think, without PPP and some other things that we did in the community with small business grants,” he said, referring to the Restart Flint & Genesee program administered by the Chamber.

That program awarded grants to small businesses in Genesee County that suffered economic distress because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consumers Energy Foundation donated $200,000 and Chase donated $20,000 to the program, while the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation provided $262,500 and the Ruth Mott Foundation added $100,000, both earmarked the funds for Black-owned businesses.

The funding was to help cover expenses associated with reopening a business under guidelines and requirements for social distancing and customer safety for businesses such as barbershops and hair salons/fitness, tattoo parlors, bars and restaurants, day care facilities and noncritical manufacturing operations.

A total of 144 businesses — including 74 Black-owned operations – received grants.

In addition, the chamber is administering the Michigan Small Business Restart Program for the I-69 Thumb Region on behalf of the Michigan Economic Development Corp. Grants of up to $20,000 are available for businesses with fewer than 50 employees and nonprofit organizations. In all, $8 million is available for a seven-county region, including $2 million designated for Genesee County applicants.

While the Chamber was not involved in administering PPP loans, staffers did help disseminate information about the program throughout the community via webinars, e-blasts and one-on-one advising.

“I can’t say enough about our team here,” Herman said. “They did a yeoman’s job in explaining just how to navigate the program and its details.”

Rossmaessler said the statistics demonstrate that local businesses were in command of the situation.

“They were paying attention and they knew how to go through the process to get a hold of this money,” he said. “They didn’t get left behind. I’m encouraged by that.”

A deeper dive

The funding benefited not just individual companies and their employees but also the entire community, said Christopher Douglas, associate professor and chair of the Department of Economics at the University of Michigan-Flint.

“I think the benefit to the community is that the Payroll Protection Program makes it more likely that businesses will survive, so you’re not left with boarded-up storefronts, vacant downtowns, vacant strip malls and the absence of a lot of businesses that the community valued,” he said.

That’s not to say that the program was the perfect solution, he said.

“There were issues with it,” Douglas said. “It was rolled out in a clunky fashion, it was tough for some small businesses without CPA firms, etc., to help them navigate the process; the first iteration ran out of money; and there’s always the risk to taxpayers that a lot of loans went to businesses that will go bankrupt anyway.

“There are certainly downsides, but given how quickly this came out in mid-March, they basically had to figure out what to do over the course of a weekend. Maybe it’s the best we could do on such short notice.”

Some individual employees might also question whether they would have benefited more from the extra $600 in unemployment benefits that the federal government also made available instead of the PPP’s job guarantee, he said. The answer likely depends on employees’ job satisfaction and whether they intended to remain with their employer over the long haul, he said.

A closer look at the Genesee County PPP figures shows that, on average, $9,248 of PPP funding was spent for every job retained.

A majority of the funds (77 percent) went to 623 businesses that received loans of over $150,000 —with four companies getting between $5 million and $10 million — while the remaining 3,239 businesses received loans of less than $150,000, including the smallest amount of $400.

Businesses in Flint, Grand Blanc and Fenton received a combined 71 percent of total funds.

“There’s a whole story behind every single one of those loans,” Rossmaessler said. “Lots of people got money, but there was a whole story for how it benefited them for every single one.”

The PPP was also a rare example of a governmental program having an immediate impact at the local level, he said.

“What happens in Washington doesn’t always trickle down to Main Street,” he said. “This affected our neighborhoods, the businesses right down the street.”