Darren McDunnough likes to joke that there are two types of green associated with his recycling-based business.

The first involves the monetary rewards of running a profitable operation, said the president of McDunnough Inc. of Fenton.

The second refers to the environmental benefits of taking pieces of scrap plastic from manufacturing sites and reconstituting them into a reusable form instead of seeing them shipped to a landfill.

Those sentiments are echoed by William J. McCaffrey, chief operating officer of Flint-based ACI Plastics, whose business model is similar to McDunnough’s.

“We like going to sleep every night knowing that you’re not only doing something to help the environment but also providing a good living for many employees while enjoying a successful business,” he said.

McDunnough and ACI Plastics are part of a growing segment of the Genesee County economy that is largely centered on recycling.

Among the newer entries into the arena are AJP Commercial Shredding and Genusee Eyewear.

Flint-based AJP Commercial Shredding, started in 2016 by April January, provides onsite document destruction and shredding to clients, such as governmental agencies and law offices. January then takes the shredded paper to a Waste Management facility in Saginaw, where it’s baled and sold to a mill for preparation to become another paper product.

While confidentiality and legal compliance are the main drivers of her business, recycling is an important offshoot, January said. “In general, recycling is important to me,” she said. “Living somewhere that’s clean and safe and environmentally friendly is important to me.”

Genusee Eyewear was born in the wake of the Flint water crisis, when founder and CEO Ali Rose van Overbeke was inspired to find new use for all the plastic water bottles residents were using. She combined her fashion industry experience and her environmental consciousness to launch a business in 2018 that sells eyewear made from recycled plastic.

“I’ve always really cared about sustainability and plastic pollution on a personal level,” said van Overbeke, a metro Detroit native who volunteered in Flint during the water crisis while on hiatus from her New York fashion design career. “I realized there was a community in my own backyard where I could possibly be a part of the solution. And I was like, OK, let’s take this waste stream created in the community and bring it back to benefit people who deserve it by providing jobs.”

Recycling Jobs

Indeed, recycling is a growing economic engine. Jobs created by companies that operate in the sector are just one measure.

For example, McDunnough has about 20 workers. For its part, Genusee Eyewear employs four people directly and also supports other Michigan businesses by purchasing recycled raw material and contracting with an injection molding company, van Overbeke said. AJP Commercial Shredding is primarily a one-person operation, although January’s father and uncle assist her and her uncle was to take on more of a permanent role after her planned purchase of a document storage company.

ACI Plastics employs about 120 workers at its four locales: two in Flint and one each in South Carolina and Nebraska. And the company is in expansion mode. It has ordered new equipment that is slated to arrive at its Davison Road headquarters late this year. Once installed, it will boost the company’s capacity to process recycled plastic by 20 million to 25 million pounds annually from its current 70 million pounds, McCaffrey said.

Supplying Manufacturers

The recycling process also helps ensure a steady supply of material for manufacturers to work with. Consider the packaging industry, for example. Robert Landaal, president of Burton-based Landaal Packaging Systems, notes that not enough trees that are planted specifically to become paper-based products mature at any one time to supply the industry. That means a steady supply of recycled cardboard, which is broken down at mills and mixed with virgin fibers, is necessary for packaging companies to meet customer demand.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) drew attention to how the flow of recycled materials was slowing as offices and many businesses shut down or were under work-from-home orders. The department urged homeowners to step up their curbside recycling efforts to help make up the difference.

That was just part of a larger public education effort by EGLE, which in 2019 launched its “Know It Before You Throw It” statewide recycling awareness campaign. The goal is not only to improve the quantity of material Michigan households recycle and increase the state’s 15 percent recycling rate — which is lowest among Great Lakes States — but also improve the quality of materials that’s recycled.

For example, campaign mascots the Recycling Raccoons deliver messages such as not putting greasy pizza boxes or cans or bottles still containing food residue in recycling bins. Such materials can contaminate and ruin a whole load of recycling.

The campaign also features hyperlocal messaging, including that aimed at Genesee County residents. For instance, billboards throughout the community urge recyclers not to place plastic bags in their curbside bins. Those are problematic because they can get tangled in recycling machinery. They instead should be dropped off at collection bins at retailers, such as Meijer, Target and Walmart, EGLE reminds consumers.

Profit Motive

For the average consumer, there’s no direct, personal benefit to recycling, beyond the satisfaction of knowing that they’re aiding the environment by keeping materials out of landfills and helping to supply manufacturers with raw materials.

That lack of direct incentive is a primary reason why consumer recycling rates are so low, industry observers say.

“Postconsumer relies on the consumer to do the work in collecting and making the effort to put it into the bin and make the effort to rinse a product out,” McDunnough said. “There’s not a lot of incentive for people to do the work, other than the responsibility side.”

The market is much more structured in the industrial and manufacturing realms.

“It’s developed over time into a pretty well-structured market with value on both sides of the coin,” McCaffrey said.

But it wasn’t always that way. Scrap produced during manufacturing was once considered junk that was destined for the landfill. Now, they know they can sell those byproducts to companies like McDunnough Inc. that will return them to a reusable form.

“The interesting side of our business is that customers are usually also suppliers to us,” McDunnough said. “What we’ve helped everyone realize is that in their manufacturing they are technically producing two products: the main product they’re producing and a byproduct of their manufacturing, which can also be an asset on their balance sheet because we are a customer of those products.

“Even though they might be scrap to them, they’re valuable commodities to us,” he continued. “What that has done is it has opened up many manufacturers’ eyes to using recycled products. The trend has inverted completely and now everyone is trying to incorporate more recycled materials into finished products.”

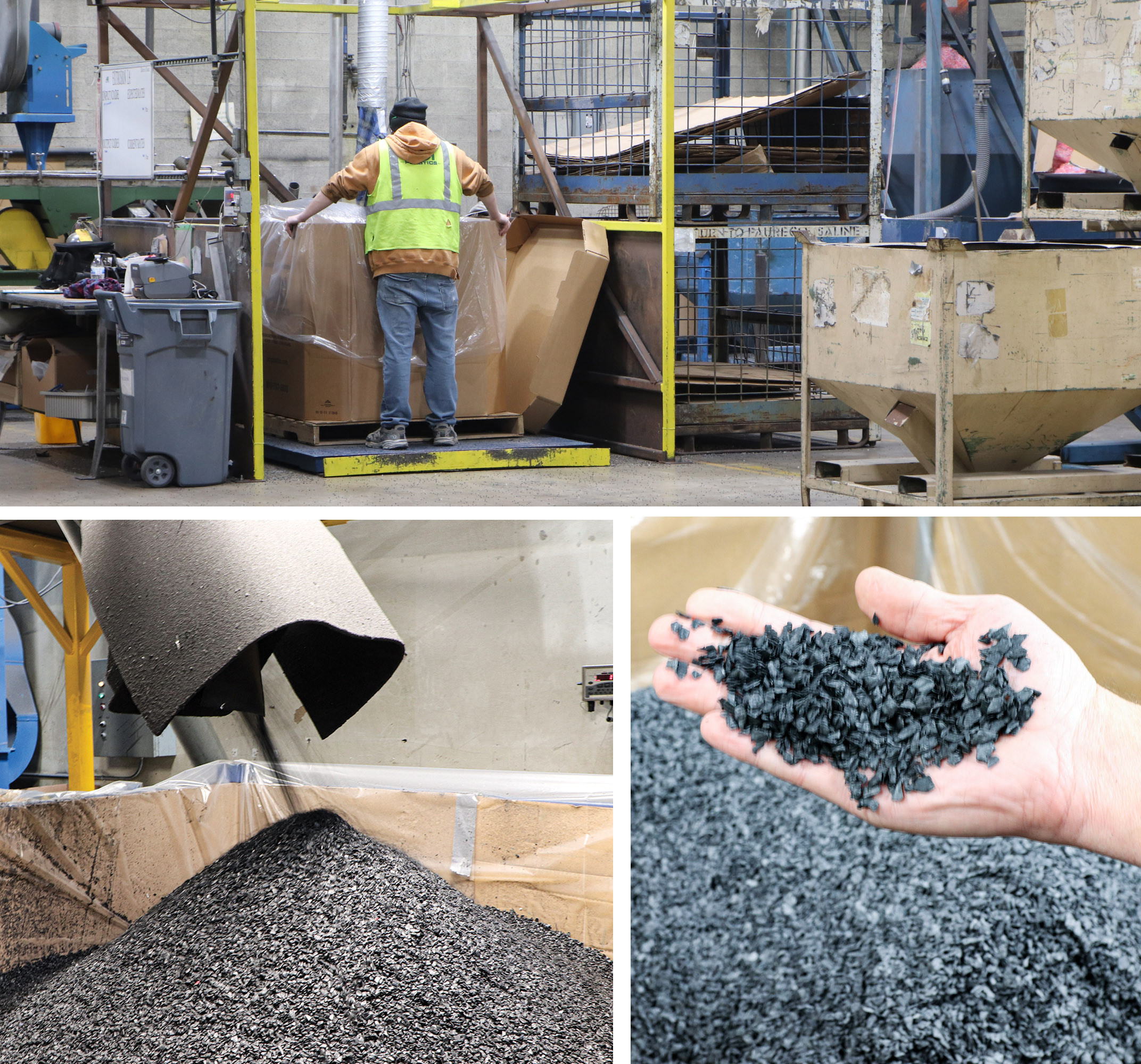

McDunnough Inc. will park trucks at manufacturing facilities, such as those operated by auto parts makers, that are gradually filled with scrap plastic and then taken back to McDunnough’s Fenway Drive operations, where the byproducts are shredded and reconstituted for use in another product.

ACI Plastics similarly prepares what was once considered manufacturing waste into a material manufacturers can reuse.

“We get them a nice near-virgin-grade pellet and send it back to them and they’ll make another molded part,” McCaffrey said.

January got the idea for her business while working in a Grand Blanc insurance office. The Oakland County shredding company that the office used provided spotty service, meaning bins would overflow with paper between visits, she said. Sensing an opportunity, January decided to start AJP Commercial Shredding.

“This was just something I was going to do to make extra money on the side,” said January, who soon realized demand was strong enough among people and business that need to ensure sensitive material is securely disposed of to support a full-time operation.

Her truck holds up to 5 tons of shredded paper, but she’ll typically empty when it’s at 3.5 tons. She’s paid for the paper, minus a sorting and handling fee.

“Recycled paper is a commodity,” she said. “It’s tracked just like the overall market is tracked.”

Van Overbeke notes that a similar profit motive exists for other recycled materials, including plastics.

“People don’t realize the recycling industry is for-profit,” she said. “When they’re recycling they think they’re doing something good, but they don’t realize it’s still based on supply and demand.”

In its own way, Genusee Eyewear — which sells its products mainly directly to consumers online — is helping to create demand for recycled material.

In the process, van Overbeke said, the company is proving the old adage that it’s possible to do well while doing good.

“We launched Genusee with the intention of doing good for the planet,” she said. “We used to get asked all the time why we weren’t just a nonprofit and our response to that is that we really believe that for-profit businesses can also do good. With as much as we’re trying to prove the concept for our product, we’re also proving that concept on the business model that shows you can do good for the planet while building a successful, profitable business.”