Ask most people how they would describe the Genesee County economy — or the state’s as a whole, for that matter — and chances are they’ll first mention manufacturing.

What they might not realize is the role agriculture plays in diversifying the types of goods that are produced here.

“Our county is not necessarily very well-known for agriculture,” said Bill Hunt of Davison Township, longtime operator of Genesee County’s largest farming operation, with 12,000 acres owned or leased throughout the region. “We’re still known for GM. Farmers as a whole aren’t really recognized locally. Agriculture isn’t talked about.”

But the agriculture industry’s contributions are certainly worth mentioning. With the notable exception of dairy farming, which has been hard-hit statewide by low prices and high surpluses, the number of agriculture producers throughout Genesee County has held relatively steady at more than 800 farming operations in recent years, providing a stable complement to the area’s manufacturing-based economy.

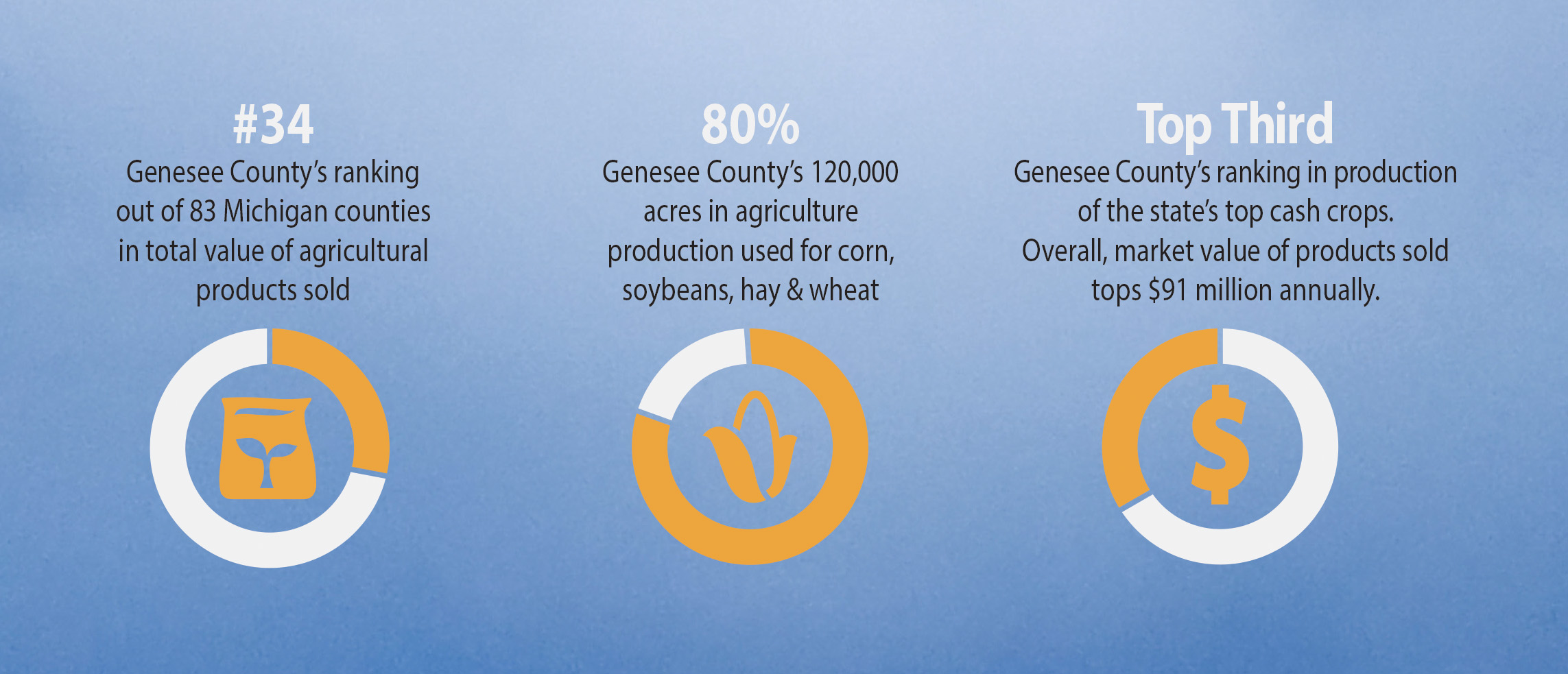

According to statistics from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Genesee County ranks 34th out of Michigan’s 83 counties in the total value of agricultural products sold.

“It’s not a major agricultural county in the greater scheme of things, but the industry is still an important part of economic diversification within the county itself,” said Bill Knudson, a professor in the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State University.

And while agriculture remains subject to the whims of Mother Nature and political policymakers, it is largely independent of overall local, statewide or national economic conditions — meaning it can serve as a reliable source of countywide revenue even when other sectors are struggling.

That’s at least partly because so many domestically produced agriculture products are sold as exports, Knudson said. “The second thing is people are going to eat, no matter what,” he said. A recession might hurt sectors of the food and agriculture industry such as restaurants, but overall demand for food will hold steady even when consumers are otherwise tightening their belts, Knudson said.

During the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and the economic sluggishness that lingered for a couple of years more, “times were decent” for local farmers, Hunt said, adding that commodity markets were buoyed when investors moved into them from stocks.

Cash crops are king

In declaring March as Michigan Food and Agriculture Month, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer noted that the food and agriculture industry contributes more than $104.7 billion annually to the state’s economy and supports approximately 805,000 jobs, roughly 17.2 percent of the state’s workforce. That total encompasses not just growers but also other agriculture-related operations, such as food processors, including Flint’s Koegel Meats, for example.

Among Genesee County farmers, the total market value of products sold tops $91 million annually, USDA statistics show.

Furthermore, Michigan’s food and agriculture industry consists of nearly 51,000 farms, 99 percent of which are family-owned, farming nearly 10 million acres of farmland and commercially producing more than 300 food and agricultural commodities — second only to California in terms of agricultural diversity.

The state also is the top national producer of several crops, including dry black and cranberry beans, begonias, blueberries, tart cherries, pickling cucumbers and squash, according to statistics compiled by the Michigan Farm Bureau.

While few of those crops are grown locally, Genesee County does rank in the top third of Michigan counties for production of the state’s top cash crops — soybeans and corn, and to a much lesser extent, hay and wheat.

Hunt’s 12,000 acres of production dwarfs that of other local growers, but his crop mix is typical: around 6,300 acres devoted to corn, 5,500 earmarked for soybeans and the remainder used to grow wheat.

Of the roughly 120,000 total acres in agriculture production throughout Genesee County, about 80 percent is used for growing soybeans, corn, hay and wheat, USDA statistics show.

Casual observers might expect what they see coming from Genesee County fields to go directly to dinner tables. But the vast majority of those crops wind up as animal feed, with a small percentage processed for human consumption (such as soy milk) or for industrial use (such as bio-based plastics).

All told, the county is home to an estimated 835 farms, which is down from close to 1,000 just over a decade ago, the USDA indicates. However, the number of farms has largely stabilized in recent years, and at least part of the earlier decline was merely the result of farmers buying out other growers, Hunt said.

One factor that has helped maintain a stable number of farms is Michigan’s stagnant population growth, resulting in less competition for farmland from other types of development, such as housing, Knudson said.

About half of Genesee County farms provide the primary source of income for their owners, while the remaining farmers might work in a factory during the day and manage their agriculture operations during their off-hours, Knudson said.

But while the number of crop growers is holding relatively steady, dairy operations continue to dry up throughout Michigan. The Michigan Farm Bureau, citing the number of dairy permits filed with the Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development, notes that the state lost 143 dairy farms from 2017 to 2018, a result of low profits, lower demand and a worldwide surplus of milk.

In Genesee County, dairy farming is now virtually nonexistent, Hunt said.

Local commodity farmers aren’t without their own challenges, Hunt said. For example, while farming equipment costs continue to rise, soybean prices are trending downward, largely as a result of the Trump administration’s tariff war with China, traditionally the top importer of U.S. soybeans.

“I think we’ve got some serious trouble coming in soybeans,” Hunt said, adding that farming has never been an easy business. “It can be a struggle being in agriculture. There are lots of ups and lots of downs. The problem is the ups are too short and the downs are too long.”

Local food for local people

While traditional cash crop farming remains the mainstay of the local and statewide agriculture industry, demand is increasing for fresh and healthy locally sourced fruits and vegetables, Knudson said.

“One of the main trends that continues to develop, especially in Michigan, is locally grown food,” he said, adding that it’s creating opportunities for smaller- scale growers to fill a market niche or boost their income.

Fueling the movement are health-conscious individual consumers as well as governmental and community organizations that are seeking to increase access to fresh foods among urban populations (efforts in Flint are highlighted in the feature story, Flint’s growing ‘gardening culture’ aiding small business and entrepreneurial development).

Westwind Milling, operated by Linda and Lee Purdy in Gaines Township, is entering its third year of operating a 2-acre community-supported-agriculture (CSA) garden, in which this year they will grow vegetables specifically for 20 customers throughout the region.

Weekly or biweekly between mid-June and early November, the Purdys will supply boxes containing a wide variety of fresh produce to clients who paid them to grow it on their behalf.

“We make food for people to eat,” Linda Purdy said.

The CSA is just one aspect of their 120-acre agriculture operation. The Purdys also lease out 88 acres to farmers who grow certified organic hay; host educational events such as bread-baking classes; and sell on a retail basis flour produced with a mill that they relocated to the farm after operating it in Argentine for 16 years.

“Our entire livelihood is based on agriculture,” Linda Purdy said. “We’re obviously about making money — you have to do that — but we’re also about community and coming together.”