Building a brighter future for Flint and Genesee County starts at home – quite literally.

“The need for affordable housing in Flint is more than just a shortage; it’s a crisis,” said Glenn Wilson, president and CEO of Communities First, Inc., a local nonprofit working to build vibrant communities through economic development and affordable housing.

“It impacts our families, it impacts our education system, and it impacts our ability to grow our community by attracting new businesses here.”

It’s a problem that’s been brewing for decades in Genesee County, in Michigan, and across the nation, experts say.

Less construction, aging housing, pandemic-induced supply chain disruption, skyrocketing material costs, inflation, high rents, and mortgage rates have all coalesced in a dark cloud over the nation’s housing market.

Today, Michigan is short about 190,000 units, according to Michigan State Housing Development Authority estimates.

And the need is only growing.

“Interventions are needed immediately in our county and in other counties across the state to make sure there is additional funding available to close the gaps on projects, whether it’s for single-family homes or multi-family,” Wilson said.

“It’s something we must do as a community and it’s something that we have to look at solving ourselves.”

All hands on deck

The good news is that innovative initiatives and new housing developments are emerging in Flint and Genesee County as public, private, and nonprofit sectors join forces to create more affordable housing – and preserve the housing we already have.

“It’s really encouraging to see more players who are working collaboratively and strategically to make the Flint & Genesee housing market more affordable, more competitive, and more attractive to a very diverse workforce,” said Moses Timlin, development coordinator at Uptown Reinvestment Corporation in Flint.

In her 2024 State of the State address, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced a plan to invest $1.4 billion to build or refurbish more than 10,000 homes. It marks the state’s largest housing investment in Michigan history.

Over the next five years, Whitmer has vowed to invest in 75,000 new or renovated units across the Great Lakes State. This commitment is needed, Whitmer said, because housing is about more than a roof over your head.

“Housing builds generational wealth and forms the foundation for success in school, work, and life,” Whitmer said. “We also know that one of the biggest factors in determining where people live and work is housing costs.”

Locally, the region needs 7,000 units to house just low-income residents alone, according to the Genesee County Metropolitan Planning Commission. Yet each year, only 100 to 200 units are built.

“At that rate, it would take 35 years to eliminate the housing shortage in Genesee County,” said Joel Arnold, planning and advocacy manager at Communities First. “It’s obvious we must do more as a community to address this growing crisis.”

Communities First has been instrumental in developing more than 250 new housing units in Flint over the last decade. Most recently was The Grand on University, a $16.6-million, new- construction project featuring 48 new apartment units and commercial space in the Carriage Town Historic District.

Emily Doerr, director of the city’s Planning & Development department, said the city is committed to addressing the housing shortage.

“Between all the federal funding sources of grant dollars plus the tax incentives and Brownfield plans, the city has committed over $40 million to help incentivize and fund either housing rehab or new housing construction in the last 10 years,” Doerr said. “That’s resulted in over 1,000 units being rehabbed or built in that time.”

Yet much of our housing is aging, inadequate for today’s needs, and expensive, Arnold said.

The persistent shortage, especially of multifamily housing, has pushed prices higher and made housing unaffordable for many homeowners and renters alike.

Affordable housing is generally defined as housing for which the occupant pays no more than 30% of their monthly income. According to Michigan’s first-ever statewide housing plan released last year, more than half of Michigan renters spend more than 30% of their income on rent each month. In Genesee County, over 70% of rental households paid more than 30%.

Studies show severely poor households are more likely than other renters to sacrifice other necessities like healthy food and healthcare to pay the rent, and to experience unstable housing situations like evictions.

A costly endeavor

A major challenge in the quest for more affordable housing is the price of construction. A new single-family home costs approximately $300,000 and a single apartment unit is $200,000 to $250,000, according to figures provided by Genesee County Habitat for Humanity and Communities First.

At that price, a seemingly large chunk of money only goes a short way. If somebody walked into town today ready to spend $10 million on an apartment development, they could build only 40 units at that rate, Arnold said.

And who can afford it? When a single person’s median income in Flint is $35,451 or $58,594 in Genesee County, those housing prices are usually out of reach, Arnold said.

Across Genesee County, safe and affordable housing is a significant concern for local housing agencies. Over 55% of respondents of a community survey rated affordable housing as a medium or high priority.

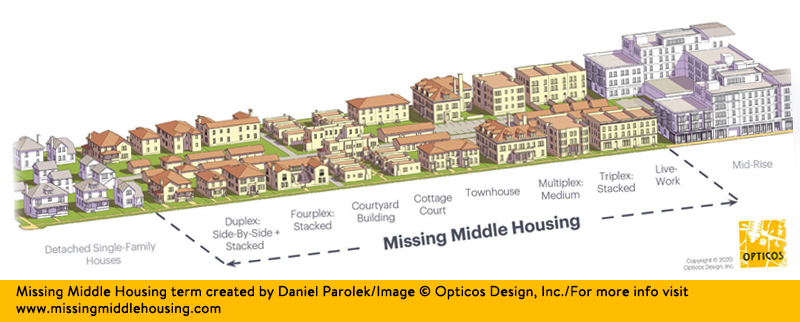

To meet the demand for more affordable housing, some communities have turned to building new “missing middle housing.” The term refers to housing types that fall somewhere between a single-family home and a mid-rise apartment building: townhomes, duplexes, triplexes, and courtyard apartments.

Once neighborhood mainstays, these housing types have been missing across America since the 1960s when modern zoning codes shifted in favor of one main form of housing: traditional single-family. In Flint, 80% of all residential lots are detached single-family homes.

But not everyone today wants a house – or all the costs and maintenance that come with it.

Generation plays an important role in housing preferences. Gen Zers and millennials are more likely to prefer an apartment or townhouse with walkability and a short commute, while Gen Xers and Boomers are more likely to lean toward a detached single-family home, according to the National Association of Realtors.

That’s why it’s important for communities to offer a range of housing types and price points.

“We need to ask ourselves if, as a community, we’re actually building something that’s attracting modern buyers and renters. In Flint, historically, I think that’s been something we’ve been missing,” Timlin said.

Finding solutions

To that end, Uptown Reinvestment has teamed up with Michigan Community Capital to build six middle-income units – two duplexes and two single-family homes – in Flint’s historic Carriage Town neighborhood. The duplexes were slated to go on the market in February.

“We’re trying to meet more of the needs of the modern buyer, but still have the spatial dimensions that allow us to build it affordably,” Timlin said.

The most immediate barrier to filling the housing gap is outdated zoning codes. Many residential areas in cities and towns here and nationwide are zoned exclusively for single-family detached homes, which makes it harder and more expensive to build new housing.

“In many parts of our community it’s not discouraged or disincentivized, but illegal to build anything except a single-family detached house, which is the most expensive kind of house to build,” Arnold said.

Loosening local rules to allow diverse housing types – duplexes, tiny homes, “granny flats” or in-law suites – and rehabilitating existing stock would go a long way toward addressing the shortage, experts say.

Understanding the need for diverse housing types and streamlined development, the City of Flint in 2022 adopted an all-new zoning code for the first time in nearly 50 years.

“It’s definitely simpler, more straightforward, and a more transparent process,” Timlin said.

The new code is a huge step forward, clearing the way for more missing middle housing, Doerr said. “The city has made progress with this new zoning code, but there’s still updates that will make it easier and easier for these types of housing to be built.”

Arnold said he encourages other Genesee County communities to revamp their own zoning codes to allow for alternatives to single-family detached houses.

Additional funding from the federal, state, and local governments will also go a long way toward tackling the shortage.

“The county has some dollars, but it’s not enough,” Wilson said. “The city has some dollars, but it’s not enough. The state has some dollars; it’s not enough. That’s the issue.

“There’s only a certain availability of funds to be able to do this work, so you have to find other creative ways to get funding to do it. Whether that’s through millages, whether that’s through tax incentives, or other means.”

Because Flint and Genesee County’s future well-being is inextricably tied to more affordable housing. After all, it plays a key role in economic development, according to Wilson.

“New businesses want to know if they build something here, is there an availability of housing stock for the people who would work and live in this community,” he said. “And if you can’t answer those questions … they’re going somewhere else.”